If one enters the world of tailoring (in any era), it is usually not long before you hear of some mythical era of tailoring when tailors could do everything with regards to drafting and fitting with their ‘rock of eye’. They could probably even make an entire suit with their ‘rock of eye’ just by looking at it, if one believes all of the hype surrounding the notion! But what is ‘rock of eye’ really, and is it of any use to the amateur tailor or home sewer who is making historical clothing for himself or a few customers? In this article I hope to shed some light on the technique and how you can apply it to your everyday sewing.

What is Rock of Eye?

During the fitting process, there are two methods used for the most part. From the ‘scientific’ end, you have patterns and drafting systems of varying complexity, focused on specific and accurate measurements, everything laid out very mathematically and precisely. On the ‘artistic’ end, you have the ‘rock of eye’ methods and techniques such as draping, which rely less on perfect measurements and more on the fitting process and the skilled human eye. Certain points will be measured out directly on the cloth and then the rest of the details and lines are added freehand. It may be a remnant of techniques used before systems of drafting were in use and everything was draped. Whatever the case may be, there are definitely some benefits to developing your own ‘rock of eye’ in order to supplement your current drafting and fitting skills.

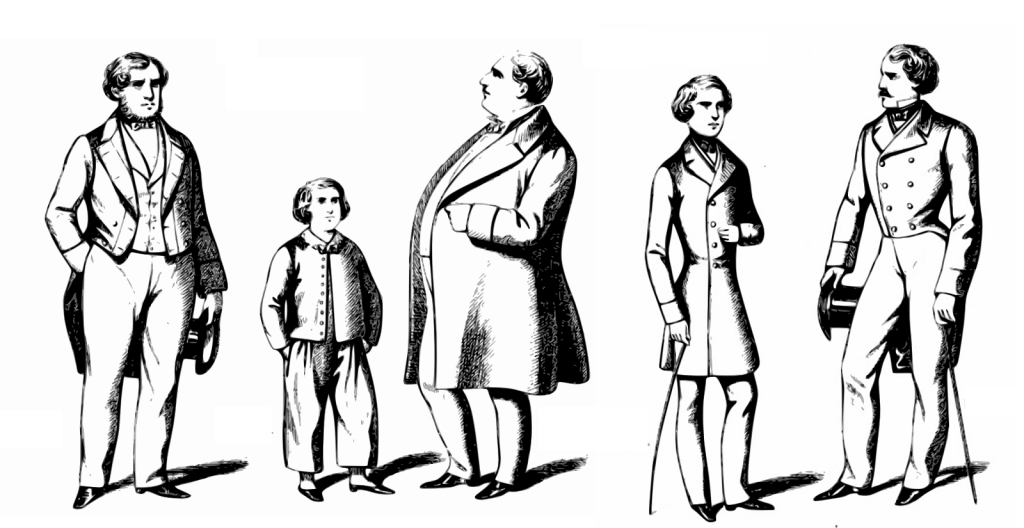

Observing your Clients

The first opportunity in which to develop your rock of eye is when measuring clients. Before pulling out the ruler, perhaps while discussing various matters related to your current project to distract your client, give a quick look at the shape of your client and the way he stands. Is he tall or short in stature? Thin or corpulent? Do his shoulders slouch forward or does he stand more erect in posture? Is he bow-legged or have knocked knees or a normal stance? It’s good to make a note on all of these aspects as accounting for them while drafting will help make the fitting process go more smoothly later on. For instance, if you know the client is on the corpulent side, you will know roughly what the pattern should look like, at least after you’ve drafted a number of coats.

Another thing you can do to help keep these details fresh in your mind is to photograph the client from the front, sides, and rear, so that you can look back and compare the photo with your notes for better accuracy.

Measuring your Clients

As you pull out your tape measure to measure your client, note the measurement you are about to take, say the chest, and then while looking at the client, estimate in your head what you think the measurement will be. Then take the actual measurement, state it out loud so as to help remember it, and write it down in your note book. Compare the estimated measurement with the actual measurement. How close were you? The more measurements on a variety of clients you can take in this manner, the better you will get at estimating, and it can help you avoid silly mistakes such as measuring from the wrong end of the tape measure. And this ‘rock of eye’ technique will further develop your eyes to aid in other aspects later on. Develop the firm foundation and build on top of that.